A wet ball flung across nowhere

Is the UK government actually going to build new things faster? How?

I never used to think I was naturally optimistic, but I had a moment this week where I thought that I might be. It came to me when I caught myself day-dreaming about living my life, this life, in pretty much the same way as I do now, except that all the things that could be fixed simply were fixed. All the skill issues were patched. The trains ran on time. No pipes dripped. My back and shoulders were loose and flexible. I thought about it some more, and then something crept in at the side of the picture. I watched it creep further. It was a small shadow. The shadow remained, and I understood what it meant. It was telling me that my dream was not in fact optimistic at all, because the dream as a form is necessarily unreal. A dream is less hopeful than prediction or a plan, and so in fact shows in its brilliance the darkness of its origin, the way it has swelled out of decay, despair, broken hinges and widening potholes.

Last week the UK government published a similar kind of dream in the form of a press release. Their dream was like mine: borne from a bleak vision. ‘Clean energy projects, public transport links, and other major infrastructure will on average be delivered at least a year faster’, they said. Something with which no one could plausibly argue. Their dream was like mine in another way: its lack of ambition testified to a greater background failure. If the government is measuring this possible speedup in years, it shows that the overall construction time has long been measured in many more years. The shadow remains at the side of the picture.

Just because the announcement is indicative of something being so broken that even the solutions are broken, that does not mean that there is nothing worth paying attention to here. The proposal specifically concerns removing the requirement to consult the public during the pre-application stage for ‘nationally significant infrastructure projects’, which means stuff like big roads, new bridges, solar farms, grid transmission, and more. You can see the full list here. There are actually at least two proposed projects to build some reservoirs, which would be the first new ones since 1992. The future is wet. To finish off parsing the phrase, ‘pre-application’ is essentially just the period before formal documents are actually submitted to the Planning Inspectorate, a period in which the developers are hearing local concerns and scoping out potential solutions to them. There is also a Borgesian requirement to consult authorities about how they intend to carry out the consultation.

All the stages in this process are listed here on gov.uk. It is noticeable that page seems to be actively pushing the public to get involved in the statutory consultation. It’s funny that the government is announcing they are scrapping something which is so endorsed by the design of their own website.

One more thing on this callout box. The quote: ‘How members of the public can get involved…’ The more I research and write about this topic, the more the word public is starting to smell a bit funny. What public even is this, anyway? Public has come to mean the kind of person who is going to read gov.uk, the kind of person to sign a petition, to read emails from government-funded NGOs. Public never seems to mean people who are busy, people who aren’t born, people who aren’t very good at English, people who haven’t moved here yet, people who are poor. So far my unease is just about the strange smell of the word. I hope that when I dig deeper into the specifics of how the public relates to the infrastructure, this smell goes away.

We shall see. But the point is that the government has proposed a change in the structure of the relationship between infrastructure projects and this public, whatever it may be. For a more expert and well-rounded explanation of the precise implications of the proposal, the best you could do would be to read the blog of Mustafa Latif-Aramesh. I won’t rehearse the whole summary here, with the exception of his insistence that the proposed changes be seen firmly in the context of the speech conditions that have obtained in recent years around UK infrastructure — or, always historicize! in the words of the late Fredric Jameson. The proposal to remove the statutory consultation period is not any kind of comment on what an ideal polity may or may not be. It is not a reflection of the UK government’s sense that ‘the public’ is of waning moral importance. It is simply a reflection of the fact that consultation has been abused in recent years, and ‘used merely as a cudgel against projects rather than to foster understanding and better quality.’

If you do historicize! it is clear that actually public consultation does not always make our projects better, and has often made them worse. Developers frequently get hit by a barrage of information requests while consulting, diverting human and financial capital away from making the actual thing work and instead towards lots of arguing about truck numbers and what times of day to do drilling. Anyway, it’s not as if the government’s recent proposals are likely to remove all public consultation. It’s going to be in a developer’s interest to do some form of consultation, and there will still be plenty of opportunity for the public to launch all kinds of challenges to development. We are a very long way from those pictures of Chinese houses in the middle of newly-built motorways with their owners remaining inside screaming at the bulldozers.

Before I started paying attention to these kinds of questions, I found it hard to understand precisely what the issue was with a few months of delay, and I especially couldn’t see the problem if the delay just meant that more consultation happened. I have worked for some years in machine learning and data, a world in which information and evaluation is simply just a good thing that is very often scarce and valuable. A world in which planning decisions were made in a richer information space would surely mean a higher quality of planning decisions, right?

It will be news to nobody that we, unfortunately, do not live in that world, but we live in this world, les meilleurs des mondes possibles, ‘a wet ball flung across nowhere’. To evaluate whether the delays and increased information density are a good thing, one must see whether the world might be better without them. Some might call it cost/benefit analysis, but I think of it more like this quote from a Bellow novel as the character and opens his eyes to things newly freshened: ‘This was the world. I had never seen it before’.

One part of this world we should see anew is a Dartford. You have never been to Dartford. If you are reading this and say, I have! — then let me impose a caveat:

you have not been to Dartford if by going to Dartford you mean you have driven from Essex to Kent, or vice versa. This is a journey that at one time in my life I had cause to make a number of times. It did not count as going to Dartford because you either go in the tunnel beneath Dartford or on the bridge over Dartford. This whole system is called, funnily enough, the Dartford Crossing. The best bit of it all is if you drive from the north to south and go over the Queen Elizabeth II bridge. Here you soar high up into the air above the stockyards and roundabouts which with windows up and with ambient industrial haze look like nothing but the loud and still forms of aliens. There are two telecom pylons to the east which stand and disappear sometimes in cloud. You race the container ships beneath you as they start their journey measured in global geometries, but it is no race at all in fact because you are orthogonal to them, on a different mission entirely, just the bee fussing about its queen. When it is me who is driving, my eye will get caught by something in this tableau because it is very beautiful, and I do mean this: my eyes get caught, and my head turns. I rubberneck at the speed of the 50mph limit, trying to see the thing I want to see, until I am nearly swivelled round, and can go like this for maybe thirty seconds before I then clock what I am doing and I snap back to attention and realise I am but four or five millimetres from the bumper in front me and slam the brakes.

I am a very good driver, so if this is my experience than you can just imagine what happens to everyone else.

It is for such reasons that for decades now the Dartford crossing has been considered perhaps the major bottleneck in the UK’s infrastructure. Last month a new crossing further east of Dartford was finally approved. This is the new project you know and love as the Lower Thames Crossing (LTC). Once completed it will double the capacity of the connections from Kent to Essex.

Last month the development was finally approved, after a planning process which generated a documentation a total of 360,000 pages long. The consultation period ended up being about 6 years. That’s very long. Try to think about what has taken you six years. What things in your life can be measured like that. I have none. My aim in Let The Dog See The Rabbit is not simply to indulge myself, but to discipline myself too, and to learn about planning and building, so I asked Gemini to be a teacher for me, and to break down what was actually happening during all these six years.

26 Jan 2016 Route-options public consultation – 47,034 responses, largest ever for a UK road scheme

12 Apr 2017 Secretary of State names “Route 3” as the preferred corridor

10 Oct 2018 Statutory consultation (10 weeks) – the formal pre-application requirement

29 Jan 2020 Supplementary consultation (8 weeks) to deal with design tweaks prompted by 2018 feedback

14 Jul 2020 Design-refinement consultation (4 weeks)

20 Nov 2020 – Highways England’s first DCO application (submitted 26 Oct 2020) was withdrawn after the Planning Inspectorate asked for further environmental and construction information

14 Jul 2021 Community-impacts consultation (8 weeks) – required because earlier rounds triggered fresh environmental concerns

12 May 2022 Local-refinement consultation (5 weeks) – minor junction changes

17 May 2023 Minor-refinement consultation (4 weeks) – residual detail tidy-up

31 Oct 2022 Development Consent Order (DCO) finally submitted; accepted 28 Nov 2022

25 Mar 2025 Secretary of State grants consent; start-on-site now pencilled for 2026 and opening for 2032

The 47,034 responses to the route-options consultation was probably the biggest cause of all the delays. There was also some faffing around in November 2020 after Highways England’s application was rejected, which meant that the full 18-month statutory process needed to restart. Once again, as someone exclusively with professional experience in the dead world of software, the notion of having to redo 18 months of work is astonishing. In tech we like to talk about which doors are one way and which are two way. In infrastructure, it appears that even doors which take you 18 months to open are considered two way.

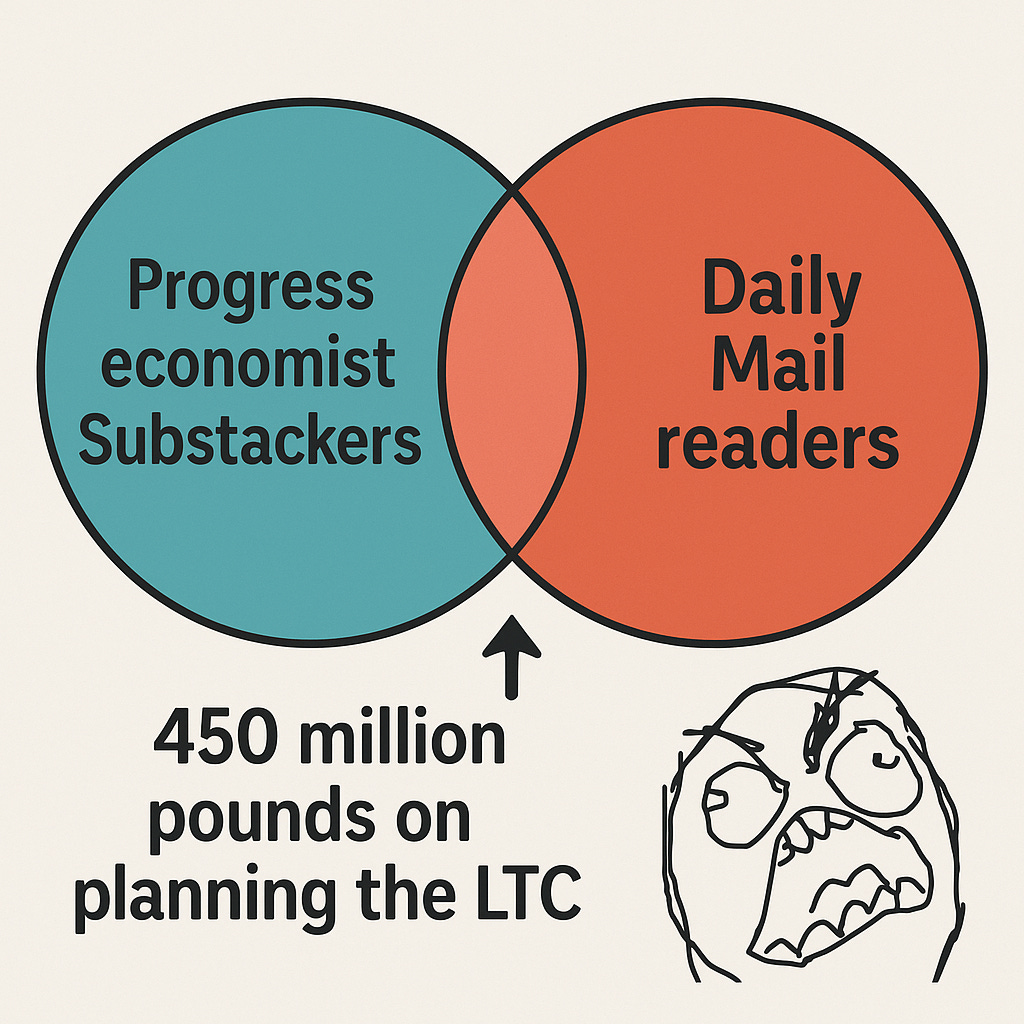

Just looking at Gemini’s breakdown of how the time was used should get anyone twitchy. The world is sometimes illegible, things are sometimes hard, but are they that hard? A reminder: the government’s proposals is trying to cut into this time sink of complexity by getting rid of the statutory consultation pre-application, which in this case started in October 2018. So what does the world look like when they have made this change? It is difficult to prise apart the exact cost of merely running the statutory consultation for the LTC. The FT has put the number at £450 million for all the documentation, but realistically the majority of this cost is not going to be recouped by the proposed changes: a lot of the spending on stuff like surveys and modelling will remain, so it is quite hard to know precisely what the monetary benefit would be. This kind of vagueness will not satisfy everyone.

However, the actual spend on this part of the process is not the most important thing. £450 million is a lot of money, and of course it would be great if things could be cheaper, but ultimately that equates to about 5% of the overall budget. The real cost of the pre-application consultation is the upfront cost as a percentage of this overall ‘planning’ spend; the real cost is in the time it takes to run and the time it adds to the project downstream in terms of complexity. The upfront cost for planning only becomes an issue if it is perceived that the planning hasn’t been successful, when nothing in particular is being delivered to anyone in particular.

Given that time is most important, I can try to compute the aggregate time cost of pre-application consulting period for the LTC. Initially there were 10 weeks of consulting, followed by 6 months for National Highways to write-up and respond to the feedback. Let’s call this 8 months together. There was also a second component, the time added the actual content of the feedback. There was a lot of feedback from our workmanlike public here: nearly 30,000 responses were received during the statutory consultation period. I wonder what happens when this public learns to use Operator or Manus, but they haven’t yet, so these responses had a countable number of zeros. National Highways actually put together a nice website to explain all of the ways that the feedback received ended up shaping the eventual design of the project. The changes involve adding extra lanes, links and connector roads, junctions, as well as moving the tunnel entrance nearly a kilometre away from the river bank. To an inexpert eye it feels like a lot. That said, I do not think I fully understand the incentives about how much National Highways want to claim they have made changes, to show they ‘care’, or whether they might think it is better to be quieter and less easily swayed, and try to suggest their plans were correct all along.

In any case, they are representing quite a lot of changes on their website, and while I am unqualified to judge whether the changes represent an increase in project quality, what we can say is that lots of them might not have been included if the consultation period had been removed. If National Highways had pressed straight from consultation close to DCO application without stopping to make revisions, the application might have been submitted in Spring instead of Summer 2020, which could have meant up to 16 months of time saving — I think1. Time exerts a cost, and each of those months of delay is a world in which the status quo persists.

National Highways have claimed that the LTC will add £40 billion of GDP to the UK. They would say something like this, of course, and that number is a best case scenario. It’s an aggregate of the value of the time-savings, safety improvements and increased reliability that the new crossing will give to the economy a 60-year period. Interestingly, to allow comparison of long-term projects with near-term ones, the benefits are discounted at 3.5% p.a., which seems like quite a high discount rate to me, but it is apparently standard for public projects. The limitations of this kind of modelling are obviously numerous. For example, projecting car usage so far into the future is complicated, especially as we might be just on the threshold of an autonomous transport revolution. Even so, if you take a conservative scenario and say that the total GDP boost per year would be about £25 billion, then you get to maybe £1 billion of extra GDP per year, which is the same equivalent output as about 15,000 full time employees. That’s like adding an extra Skipton to the UK economy (putting it that way is maybe not making my point. I would say I’m still a fledgling economist). All these extra Skiptonians translates to greater national productivity, more tax revenue, all the kinds of things that a minister would say on Radio 4, but that are no less desirable for that.

There is also a wider cost to our wet ball flung across nowhere, and that comes in the form of carbon. Delaying the LTC by 16 months means there is going to be 16 more months of cars delayed and idling around Dartford given its accident-prone nature. This is about 66,000 tonnes of CO2 extra being emitted per year, which is the same as about 40,000 London to New York flights.2 This is clearly a climate disaster, and it means delaying this new piece of infrastructure is an emergency. Here is a picture of some people agreeing with me, demonstrating in favour of the new development.

Of course not, you idiot. These are the people from Thames Crossing Action Group, one of the most important pressure groups trying to block the LTC. They have spent years launching legal action against the project, taking every opportunity afforded by the process to try to delay and obstruct. This is the public my nose was warning me about. These are the people who are engaging. And their engagements are very interesting, which is not to say correct. They make a number of arguments about the expected carbon cost of the project, the impact on local habitats, and the low expected benefit to the extant traffic problems, but the sheer accumulation of so many arguments makes it difficult to believe in any single one of them, because the pretence that the LTC has been considered purely on its merits becomes harder to sustain when the group takes issue with literally every possible component and variation of the project. Furthermore, many of the arguments are simply mutually contradictory: sometimes the group says the issue is that the LTC won’t take enough car traffic, yet at other times they say a train-line should be built instead which will of course not relieve any car traffic at all. They complain about the massive costs of the crossing while doing everything they can to block it and make it more expensive.

The picture of the protesters does make me sad. Climate politics has become bundled in with a number of anti-building prejudices in the UK which means that its politics are very often self-defeating. Liberals and economic progressives have failed to convince people that there can be an efficient and newly-built world which is carbon positive. Writing Substacks will not help with this.

Stating that this public is wrong about development and infrastructure is not trying to explain away the fact that many of them will be losing in out in some meaningful way. This shouldn’t be forgotten. Landowners and householders in few kilometres’ radius of the proposed crossing will probably be poorer. This is actually not a good thing, and they are justified in making noise about it. Nothing in particular gives me the right to say from my desk who are the people who should win and lose. I have not been ordained as the man who picks the chosen and the damned. So I don’t really have much to say to these people. I would be sad if it was me. I hope I would be able to trust in my government that the benefits would diffuse, that the wealth would spread, that for each non-congested car trip a little prayer of thanks was said to my village, but I don’t feel confident that that would be the case. Ultimately there is a curtain, and I am on one side of it. I am in this world, and this is one I have seen before.

This is assuming they spent about 3 months (Dec 2018–Mar 2019) analysing the 28, 493 statutory‐consultation responses and publishing the report, then roughly 10 months (Apr 2019–Jan 2020) on reworking designs, traffic and EIA updates for the supplementary consultation. This is like 13 months? Then maybe you add a further 3 months for related messing around and document writing. Not sure. Advice on these calculations is received gladly.

Gemini’s calculations: Assume an average fleet mix of 85 % cars, 10 % light vans and 5 % HGVs.

Typical idling or slow‐crawl emission rates:

• Cars ~2.0 kg CO₂/hour

• Vans ~3.0 kg CO₂/hour

• HGVs ~4.5 kg CO₂/hour

Fleet-average rate = 0.85×2.0 + 0.10×3.0 + 0.05×4.5 = 2.2 kg CO₂/hour.

Total saving = 30 000 000 h × 2.2 kg/h = 66 000 000 kg CO₂ ≈ 66 000 t CO₂ per year.